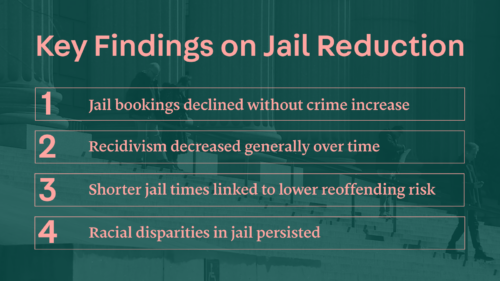

Four findings from our new research on the impact of jail reduction reforms on public safety.

Reducing the use of incarceration and implementing new approaches can strengthen public safety, our new report finds. In partnership with the MacArthur Foundation’s Safety and Justice Challenge, the report studied the impact of reforms that reduced the use of jail in two communities: New Orleans and Lucas County, Ohio.

The reforms were far-ranging—from diversion programs that connect people to community-based treatment instead of jail, to a validated risk assessment tool that helps judges make more informed decisions about whether someone can be safely released. There’s mounting evidence that alternatives like these can keep communities safe while reducing the harms of the justice system.

Here are four takeaways from the report that shed light on the relationship between jail reforms and community safety.

#1: Incarceration can be avoided without negatively affecting safety.

“Tough on crime” rhetoric often suggests that reducing the use of jail inevitably leads to more crime. Yet in both of the jurisdictions we studied, there was no evidence that shrinking jail populations jeopardized public safety.

The report compared jail bookings and crime rates in the period before and after the reforms were launched. It found that jail bookings steadily declined following the reforms, with no corresponding increase in crime.

In particular, people charged with lower-level, non-violent offenses were less likely to face jail time after the reforms. Given the countless ways jail can make it harder for people to thrive, that unsurprisingly leads to more—not less—safety.

#2: Recidivism rates generally decreased following the jail reforms.

One important measure of safety is recidivism—the likelihood of someone being rearrested after an encounter with the justice system. In both New Orleans and Lucas County, recidivism rates went down after jail reduction strategies came into effect.

Recidivism for felony offenses dropped from 23% to just 6% in New Orleans over the course of the study. In Lucas County, they went from 18% to 13%. Recidivism also dropped for felonies classified as violent, which have the most direct impact on community safety.

#3: Less time spent in jail means greater public safety.

In addition, the report found that less time in jail was associated with lower rates of recidivism. People who spent more time in jail on an initial booking were also more likely to be incarcerated again.

In other words, longer jail stays may actually make communities less safe—and vice versa.

That tracks with what we know about the harms of jail, which often leave people even worse off than when they came in. It’s also consistent with other research showing that incarceration can increase a person’s odds of coming into the system again.

#4: Racial disparities in incarceration persisted.

While jail bookings decreased overall following the reforms, racial disparities in jail populations persisted over the course of the study. In both communities studied, people of color were twice as likely to face jail time compared to white people.

This finding confirms that reducing the use of incarceration overall doesn’t necessarily reduce racial disparities in jails. Without proper care and attention, diversion programs and other reforms can even end up exacerbating those disparities.

This new report adds to a growing body of evidence that confirms what those most impacted by the system have long known: jail doesn’t make us safer. Reducing the use of incarceration isn’t just compatible with safety, it’s an essential part of it. And that must go hand in hand with developing proactive, data-driven strategies to address the persistent challenge of racial disparities.