Subscribe on Apple Podcasts → Spotify → YouTube → Pocket Casts →

That’s one way of describing restorative justice—it’s about helping people become unstuck.

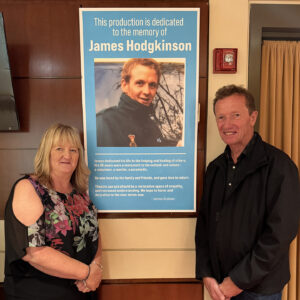

Jacob Dunne was 19 years old when he threw a single punch at James Hodgkinson outside of a bar in Nottingham, England. After falling to the ground and hitting his head, James lost his life just nine days later. He was 28 years old.

In the aftermath of that loss, James’s parents—David Hodgkinson and Joan Scourfield—had a lot of unanswered questions. So they reached out to Jacob through a restorative justice organization, after his release from a young offenders prison.

Jacob agreed to answer their questions, opening a dialogue that would grow into a remarkable partnership—with the three of them working together to raise awareness about the dangers of one-punch manslaughter and the power of restorative justice to help people find a way forward after serious harm.

It’s a story, not so much of forgiveness, but of something richer, more complicated, and even more deeply human.

Now, that story has made it all the way to Broadway in the form of the celebrated play “Punch,” produced in New York City by Manhattan Theatre Club. Our restorative justice team has partnered with the production to facilitate some of the post-show discussions.

In this episode of New Thinking, we’re joined by the real people behind this powerful play: Joan Scourfield and David Hodgkinson, the parents of James Hodgkinson; Jacob Dunne; and Nicola Fowler, the restorative justice practitioner who has been a part of their journey since its beginning.

Learn more about restorative justice at the Center for Justice Innovation.

The following is a transcript of the podcast:

Matt WATKINS: Welcome to New Thinking from the Center for Justice Innovation. I’m Matt Watkins.

In 2011, Jacob Dunne threw one punch at James Hodgkinson. They were outside of a bar in Nottingham, England. James, 28 years-old, fell heavily to the ground—his head striking the concrete. Nine days later, James was taken off life support.

Jacob pled guilty to manslaughter. Nineteen years old at the time, he served 14 months in a young offenders’ prison.

Along with grief and anger, James’s parents were left with a lot of unanswered questions. After Jacob’s release from prison, David Hodgkinson and Joan Scourfield contacted Jacob through a restorative justice organization.

Jacob agreed to answer their questions. That opened a dialogue that took place initially only in writing, all of it facilitated through a restorative justice practitioner.

But over the years, that relationship has grown in some truly unexpected directions. The three—Joan, David, and Jacob—teamed up as advocates, speaking publicly about the dangers of one-punch manslaughter, and about the power of restorative justice.

What’s more, the British playwright, James Graham, came across their story and transformed it into a celebrated play, Punch. It debuted in Nottingham, before making its way to London’s prestigious West End. And now Punch has just opened on Broadway in New York City, being produced by Manhattan Theatre Club.

At the Center for Justice Innovation, we’ve long been practitioners of restorative justice. In recent years, we’ve turned increasingly to using restorative justice to respond to cases of serious harm and violence, as in the death of James Hodgkinson. So we’ve been honored to partner with the New York production of Punch, helping to facilitate some of the after-performance discussions with audiences.

I was also very happy that this partnership brought the real people behind this production into a studio to talk about the journey they’ve been on, and the message they want people to take away from their unlikely collaboration.

Joan Scourfield and David Hodgkinson are the parents of James Hodgkinson. They joined me in person, as did Nicola Fowler. Nicola, with the UK group, Remedi, is the restorative justice practitioner who has been part of this story since the beginning. And Jacob Dunne joined us remotely from his home in Nottingham, England.

WATKINS: Well, Joan, David and Nicola—and Jacob, who’s appearing virtually here that we can all see—it’s just such an honor and a privilege to have you here, and I just really appreciate you all taking the time to share this remarkable story with us.

David HODGKINSON: Thank you.

Joan SCOURFIELD: Thank you.

Nicola FOWLER: Thank you.

WATKINS: We’re going to talk today about this single act of violence that occurred that tragically brought the three of you together, but I just thought before we did that, that it would be good, Joan and David, if you wanted to talk for a minute about your son, James, about who he was so people have some understanding of that.

SCOURFIELD: James, at the time of his death, was 28 years old. He was on the cusp of becoming a paramedic, had done quite a few of the exams—he just got one more to do. He was enjoying life, living in London. He liked the fast life. He was very much an adrenaline junkie, used to go out windsurfing, wakeboarding, downhill biking, skiing—always a big worry when he went on these adventurous holidays.

WATKINS: I was going to say, that would be a bit nerve-wracking!

SCOURFIELD: Yeah. Always a big worry. He had a very, very strong family, his connections to his family—always coming back home for events, always regular text messages and phone calls, and a huge, huge group of friends, right from school till when he was a paramedic.

HODGKINSON: Yeah, I’m so proud of James and everything that he achieved, and I think he achieved so much—more than a lot of people do in a long life, he achieved in the short time he was with us. Very loving son. He was very passionate about his work, and a hard job working for the London ambulance: he was dealing with very difficult situations.

I think he was very suited to that because, yes, he was someone that liked a bit of a buzz in the work and a challenge, but he was succeeding in everything that he wanted to do. And very family-oriented, as Joan said. He liked to send little jokes on WhatsApp and little messages and things, and we’d have phone chats.

A wonderful son! And we were very lucky to have the time that we did have.

WATKINS: I should just say, I’m just so sorry for your loss, and again, I just very appreciate you being here.

Jacob, I know this is something you’ve done a fair bit of thinking about: Do you want to talk a little bit about what you now understand about how you grew up and the sort of culture of where you were and who you were and how that led in some ways to this tragic encounter that you had with James?

DUNNE: I do believe that a lot of it is about cultural views and how people learn what’s right from wrong, and just how acceptable everything seemed to be back then. And that going to prison was like a badge of honor, and having a criminal record was something to be proud of, and just wanting to always get adrenaline from being chased by the police or being in some sort of altercation or drama.

Where I was brought up was a place called The Meadows, which is like a council estate, what you’d kind of say over there is like a project, I think.

WATKINS: Like public housing.

DUNNE: Public housing, yeah. And there’s a river called the River Trent that runs through my estate, and on the other side of the river, there’s a suburban neighborhood where people, on average, life expectancy is 10 years higher, and I can throw a stone over the river.

And I think that’s just a statistic that puts into perspective the issues that have embedded culturally into that place that I grew up. The belief that you can apply yourself and get educated and progress, and social mobility, don’t really exist much.

And I don’t really like talking about the context, because I’m a big believer now as well, not using things as a… Trying not to use those things as excuses in terms of explaining crime, but the context is important. And I was: brought up by a single parent, witnessed domestic abuse, exposed to violence, dropped out of school, was diagnosed with ADHD, dyslexia, mild autism.

And so the list just goes on really. And then you just, with a lot of other young people who, in often cases had more extreme poverty and more extreme childhood experiences than I did, and we all just were a bit lost and directionless and didn’t believe in the mainstream way of living life, which is to get a job, do a nine-to-five, pay taxes. That didn’t really appeal to any of us.

WATKINS: And can you take us back to that evening in July 2011 when you have this one-punch encounter with James, just so people understand what took place?

DUNNE: I was on a night out celebrating a friend’s birthday. I had been heavily drinking, taking substances throughout the day. And then late in the morning, I got a phone call from a friend who falsely called me and said to come and help him out, and that it was kicking off. And so I went running to the scene to where he was, and then just impulsively threw a punch, without thinking of the consequences or even thinking about de-escalating the situation or trying to gain an understanding as to what was going on.

And then I ran away from the scene and wasn’t aware of the consequences of what happened until I was arrested. How long later? A month later?

WATKINS: He fell from the punch and hit his head and that’s-

DUNNE: Yeah.

WATKINS: Yeah. But you weren’t aware of that at the time?

DUNNE: No.

WATKINS: No. But I’ve seen where, I think it was maybe in an initial draft of the play, it was described as a “tragic accident,” and that you all pushed back on that language. You as well, Jacob, you don’t want to see it described as a-

DUNNE: You can’t throw a punch accidentally.

HODGKINSON: I have a big problem with that term.

WATKINS: For sure.

HODGKINSON: I’ve discussed it with Jacob quite a lot. You don’t accidentally punch somebody and that full stop. You accidentally bump into somebody. It’s a conscious decision, and yes, that night Jacob was not, because of the drink and the substances that he’d taken, was not thinking straightly at all. And obviously I witnessed the assault.

WATKINS: Right, we should say you were right beside James-

HODGKINSON: I was there, I was in the doorway of the bar, Yates’s Bar. Actually, the reason for that was that you weren’t allowed to take alcohol out onto the street. So, we got some beers, so I stayed with the beers just inside the building, and James had gone out to chat to this group of lads.

And as is mentioned in the play, we’d been to Trent Bridge for cricket, and we’d gone dressed as pirates, which is a thing we do in the UK…

WATKINS: I did not know that.

HODGKINSON: You don’t have to be a pirate! You could be any group, you could be a fireman or whatever. You have a theme thing. It’s a bit of fun when we go to international test matches.

And part of this outfit… We’d left it on a table in the bar, and some of the guys had taken some of these bits and it was no kind of problem with anything. And the police actually went into this subsequently from the CCTV in the bar to see if there’d been any sort of interactions or there’s any reason that we’d had a problem with Jacob’s group as such, prior to this happening. And we hadn’t.

So it was very unfortunate that Jacob was given the wrong information. He wasn’t in a clear-headed state, and of course steamed in without understanding the situation that he has been presented with. James had his hands down in a non-violent, non-confrontational position, and when Jacob hit James, he just went down straight away. And yes, his head hit the concrete. And that is the problem with one-punch, because if you’re knocked out, as he was at that point, and you’re just a dead weight dropping then to the ground, there’s a lot of force.

And of course that causes trauma, trauma to the head. Very, very difficult thing to see. And I chased after Jacob. But of course, big age difference between us. And again, as shown in the play Punch, Jacob has found a hiding spot, and of course he didn’t know at the time the damage that he’d done.

And it was nine days later that we had to switch off the life support.

WATKINS: Nicola, do you want to talk for a minute? I’m just struck by… I mean, Jacob, I think I’m right, that you were sentenced for manslaughter in part because it was ruled you weren’t intending to kill James.

DUNNE: Correct.

WATKINS: Correct. Okay, so the focus that restorative justice has on genuine accountability would mean that this language of “tragic accident,” that we’re all agreeing is not the right language… But do you want to talk about how you understand that in a restorative justice framework and how we think about accountability, and the journey Jacob’s been on in that respect?

FOWLER: Sure. For restorative justice to happen, you’ve got to have that minimum acceptance of responsibility, which Jacob did have, he accepted that he had-

WATKINS: Even initially you’re saying.

FOWLER: I mean, he pled guilty. He accepted that he threw the punch, which caused the death of James. And when we met with Jacob for the very first time, it was clear that he felt remorse. But I think it was the first time that he had stopped to really think about that full impact because he’d not necessarily been challenged around that in custody.

And accountability is important because if we were to put anybody in that situation where that accountability didn’t exist, that could cause further harm. And restorative justice is about repairing harm. If we had gone to see Jacob and he had minimized what had happened—he justified his actions or blamed James in any way—we would’ve needed to consider whether restorative justice is even appropriate.

But certainly with Jacob, that was clear to see that first time that I met him that he fully accepted and wanted to take part in restorative justice because he saw it as something that he should do for Joan and David.

And as a restorative justice practitioner, we will often say, “What do you think this could bring for you? What benefit could that bring for you?” Because it’s about everybody gaining something from the process. And Jacob said, “It’s not about me, it’s about them. I’m doing it for them.”

But I think as part of that journey, we’ve certainly seen that it’s helped everybody involved.

WATKINS: Joan, I’m wondering, could you talk for a minute about how you… I mean, there was this standard criminal justice system response to what happened, and I’m just wondering how that left you feeling in terms of your needs as a victim, as a mother of James, how your needs as a victim were met?

SCOURFIELD: We had a lot of questions about the night and the justice system couldn’t answer them. The police did a very good job in finding Jacob, because obviously Jacob had run off. They had to go through CCTV to find what he was wearing and what boy they thought had done it. And they’d done a very good job in doing that.

But they’re not worried about the victim’s feelings and what questions they want answered. So we had lots of questions about the night: why Jacob had done it, and different things that we couldn’t get answers to.

When he went into prison, obviously, we felt very bitter and angry about the sentence that he got. And then inside we wanted to know how did Jacob feel? Did he feel any remorse for what he’d done? Was he going to come out and do this again to another person? Was another family going to be put through what we’d-

WATKINS: Right. That was a major concern for you.

SCOURFIELD: Yeah, major, major.

WATKINS: Restorative justice is focused on preventing future harm.

SCOURFIELD: Yeah, I knew nothing about restorative justice at all, nothing. And then victim support offered it to us, and we took up the restorative justice from them in hope that Jacob would come with us and answer our questions. That’s all we wanted at the time, really, was a bit about what he was going to do next and answers to the night, really.

HODGKINSON: One key important thing here is that, with restorative justice the victims get answers that they can’t necessarily get by any other means, but also for restorative justice to help the perpetrator of a crime. So we’ve not got this vicious circle of just doing some prison time, coming out, reoffending, back into prison.

And when in prison you are just learning more and more bad ways, you’re getting bad influences. With restorative justice—and I think Jacob is a shining example of how we can break that horrible cycle and have a person that’s started from a very bad situation and now be somebody that is such a benefit to society.

It’s a win-win for everybody, and this is why we want to promote more and more of this.

WATKINS: And Jacob, your time in prison, as we’ve been saying, was relatively short, certainly by U.S. standards, but you got out, you’re probably in worse shape than when you went in.

What was your feeling when you first heard, I guess, through Nicola and her organization, Remedi, that the family of the victims wanted to be in touch with you? I mean, that must have been something of a shock.

DUNNE: Yeah, that was a huge shock. I used to think… Well, on the rare occasions I did think about the impact of my crime, I would… Well, I just don’t think we can get very far down that road without actually understanding it—the truth—from the people you’ve harmed mouths themselves.

And if we want people to be more accountable in general, then I think they’ve got to know what they’re being accountable for and be aware of the harm they caused. But if people are ignorant and unaware of the harm they cause then… What’s that saying, “ignorance is bliss,” isn’t it? It’s easy to stay there.

But for me, having that request come in from David and Joan stopped me being ignorant anymore and allowed me the opportunity to genuinely, safely think about the harm that I caused instead of being asked to imagine it.

WATKINS: Right. I mean, ignorance is bliss, but the knowledge that you got of the harm that you’d caused, that’s obviously not bliss either. That’s very hard to hear.

DUNNE: No, no, it’s not bliss. But the truth will set you free eventually. But it was, yeah, I needed it, I needed that. It wasn’t easy. It would’ve been easier to ignore it or say no to the request, but then I would’ve stayed stuck. And I don’t want to speak on David and Joan’s behalf, but I know that was part of the reason that they requested it was because they felt stuck.

So this was about being unstuck. That’s one way of describing restorative justice. It’s about helping people become unstuck.

WATKINS: And Nicola, you were sort of overseeing or facilitating all of this, for the first, I think maybe two or three years, the communication between Joan and David and Jacob is all happening through letters or written questions, and then you’re there delivering each time to each party. Do you want to talk a bit about how that worked and then, I don’t know, maybe the content of some of this correspondence, it’s a long time.

FOWLER: Definitely. Well, it was myself and a colleague, Jan. We always work in twos because to ensure restorative justice is safe, we have two impartial practitioners. And it started initially with an initial assessment meeting with David and Joan to understand what they wanted from restorative justice and what their needs were, whether they wanted to engage through ourselves indirectly—sending messages, letters—or whether they felt comfortable meeting—which, at that early stage, both David and Joan said it could be 10 years before we feel comfortable to meet Jacob.

And then when we went to see Jacob, the first step is understanding, is he willing to participate? Is he willing to hear from David and Joan and-

WATKINS: Right, because everything has to be voluntary here or it’s not restorative justice, right.

FOWLER: Exactly. So he could have said no. And there’s a lot of work undertaken to manage some of those expectations in those early days and safety plan around that because the last thing that we want to do is to cause further harm, but often giving victims an opportunity just to request this can be quite empowering.

So when we went to see Jacob, it was an opportunity for him to consider his involvement, which he agreed to straight away. And in those early meetings, David and Joan had given myself and Jan permission to share some of the motivations that they had around restorative justice, some of the initial questions that they might have.

And Jacob gave us permission to share what he spoke to Jan and I about in terms of how he was feeling—but not only what he said, but how he presented. So it felt important to Jan and I to share with David and Joan how emotional Jacob was in that first meeting, because it was really clear to us that he was feeling extreme remorse and regret, and was really reflecting on his behavior.

So we shared some of Jacob’s body language and how he presented during that initial meeting. And then that led to a process where we looked at more detailed questions and specific things that David and Joan wanted to know because there is only literally that one person that can answer those questions. And those questions are very personal, they’re very different in every restorative justice case.

And Jacob initially responded verbally, and then he spent some time writing a letter, which I remember sitting with yourself, Jacob, in your apartment. I think we spent about three hours going through what you wanted to say.

He was really invested in making sure that he answered David and Joan’s questions properly and fully, and then facilitated ongoing communication at the point that David and Joan asked, “What do you want to do with your life going forward?” And then it was more updates in terms of Jacob’s progress and what he was doing and leading up to the point where they felt comfortable to arrange that face-to-face meeting.

WATKINS: Yeah, that seems like a really remarkable moment, that moment of asking Jacob, “Well, what do you want to do with your life? What are you going to do?” I don’t want to be too influenced by the play, but I thought the way they end the first half with that question being asked by the person playing you, Joan, “Jacob, what are you going to be?” And then the sort of lights drop.

Did you realize at the time how consequential asking that question would be? It just seems like such a big step in some ways.

SCOURFIELD: No, it was more that, what do you want to do with your life in that you’ve done the worst thing, what are you going to do now and try to address, we don’t want this happening again. And look at how you can change. And that’s what people have to look at. If they’ve done wrong, there’s always another way forward. If you don’t want to stay on the wrong path, there is a way you can change.

HODGKINSON: A hundred percent. So from two sides, I think we were so angry and frustrated because we couldn’t get any answers. So it was just why has this person done this to our son? But I think then once we had got our answers and I had so much anger and I was in a really bad place without getting that knowledge.

But once we started to understand about Jacob through the communication, and you do start to think about him and his family, and I think then, yes, that that was the big question that we wanted to know: what are you doing with your life? And we weren’t expecting to end up where we are today. I mean–

WATKINS: I would think not!

HODGKINSON: It’s incredible, the road that we’ve traveled together. But we just wanted Jacob to make something of his life, to not just stay as he was in this terrible situation, go back to the gang. All the things that he hasn’t done were the things that we were hoping for. So it’s such a great result for everybody.

And obviously we appreciate how hard this has been for Jacob to achieve. It’s very easy just saying this, but that was not an easy thing for Jacob to go back and get all the education and do everything he’s done.

And for me personally, not having the anger, that was a great gift that Jacob’s given me. I mean, he took James from us, and we’ll never get over the loss of our son, but it’s enabled myself to… I can live my life. I’m not a bitter person. I’m okay. I’m enjoying my life. I mean, you never get over the loss of a child–

WATKINS: No, of course not.

HODGKINSON: …but we’ve been able to move forward. And if Jacob had said no and not participate in this, we would still be in that not-knowing land: Why did this happen? No answers.

And I think I’d have still been very, very bitter, very angry, frustrated person, and probably that would’ve affected my interactions with everybody else and how I’ve moved on with my life in the last decade-plus since this happened.

WATKINS: Jacob, how important then for you was that question and that interest that Joan and David are taking, in terms of everything you’ve done since, which is an impressive list, first-class honors degree in criminology and author and podcaster and father, how do you understand that? I guess an open mic question for you to talk about Joan and David for a moment.

DUNNE: Yeah, you would never think that there could really be a single question that could have such a pivotal moment in your life and such a big impact on your future trajectory. As I said before, just about how shameful I felt, how bad I felt, and how pessimistic I was for my life prospects in the future.

David and Joan asking me what I was going to do with my life and just showing an interest or caring about me at all made me think, “Well, I’ve got to care about me. If they want me to do well, then the only way I’m going to do well is if I start caring about myself and taking their care and applying it to myself.”

And then that was the start of the journey then, I think I sat there and was like, “Right, I’m going to go back to school and get an education.”

WATKINS: Nicola, this all leads then to the first in-person meeting, which again is a few years after contact had first taken place. Do you want to talk about what led to that personal encounter, I guess, sorry, and I guess from a restorative justice standpoint, how you structure that and manage that.

FOWLER: Sure. Well, Dave and Joan had initially, as I said, thought that they probably wouldn’t be ready to meet for at least 10 years, but through that communication and I suppose building a picture of Jacob, seeing that he was progressing, they said when he’s progressed to a certain point, maybe before he starts university, once he’d got his place at university, that they felt that they would be then ready to meet.

And we’d done a lot of work with both David and Joan and Jacob to prepare for that meeting: thinking about where the meeting’s going to take place, how the room’s going to be set up, who’s going to speak first, what do they want to focus on?

You’re not only preparing for your own emotional response, you’re preparing for the other person’s emotional response, and that can be really difficult. And we have time with David and Joan before we bring Jacob into the room. And there’s always somebody sat there with David and Joan so that there’s that support for both people.

But ultimately it’s their meeting. And the only role that we would need to play in that meeting is if we needed to intervene or to ensure that people needed a break, if we could see that they were struggling.

And then at the end of the meeting, it’s a chance to talk more relaxed, which was really… For Jan and I to witness that, it’s essentially a formal meeting, but then they had a drink, we’d taken snacks because it’d been a long journey for everybody. And they sat and started communicating more relaxed and thinking about the campaign and where they wanted to continue to work together, which as a practitioner to see is amazing. And then where that’s gone is even further.

WATKINS: You mean the idea of working together and trying to get something good out of this, that emerged from the very first in-person meeting, this kind of conversation that takes place after the hard stuff has happened?

FOWLER: It was clear to see from the moment that we met Jacob, and then the initial communication started happening, that this could be a really powerful restorative justice case and that there could be some campaigning work that they would do around one-punch manslaughter.

I saw some of that happening and there was that initial… Joan and David had already done so much awareness work themselves: David had done a bike ride, hadn’t you, to raise awareness and funds.

We knew they would do something, but never quite to the extent that they have. And it was during that meeting that they agreed to share their contact details so that they weren’t necessarily needing to communicate through us as practitioners, but they could ensure that they were able to contact each other going forward.

WATKINS: Joan, can you remember what you were looking for from Jacob in that first meeting?

SCOURFIELD: My very first picture of Jacob was the mugshot. I don’t know if you have mugshots here.

WATKINS: We do, unfortunately, yes.

SCOURFIELD: So that’s not very flattering for everybody, but that’s what you’ve got in your mind, just that picture. And then walking into the room, he was a very young, vulnerable young man. That’s how I… From this hard picture of a mugshot to this young, vulnerable young man walking into the room. That’s what really hit me the most, I think.

WATKINS: And what was it you wanted him most to… I mean, you’d already had three years of this mediated communication, but what was it you wanted to most understand?

SCOURFIELD: So when he said he was going to turn his life around, I looked at it a bit like a diet. So he was changing all these things, and he had a lot of things happen in his life. He had family loss and different things, and every time something happened, I thought, “Was he going to slip through the net and go back to the gang?” These were all the people he’d known all his life and was he going to give up the education and this new life and go back? What was easier for him?

When you are going through a loss or bereavement and things yourself, you might need that old comfort. And I think to see him, after we’d done those three years and he was then going on to university, and he said, “I’m going to university for you.” I said, “You can’t go to university for us. You’ve got to go for you. We don’t want… It’s not the degree that changes the person, it’s the work you’ve been doing that changes the person.”

WATKINS: Which I mean in restorative justice, you have to do it for yourself, not for anybody else.

SCOURFIELD: Yeah.

WATKINS: Jacob, I’ve seen, I think, where you described that meeting as sort of, you say something like “the power dynamic shifted as a result of that meeting.” I’m wondering what you meant by that.

DUNNE: I think the power dynamic shifted from Nicola first coming to see me in my probation office. But by the time we’d met for the first time, if you were an outsider looking in, you could probably just see the power dynamic actually shifting.

Yeah, I was just like, “What am I doing walking in this room?” I wanted to go in the room, but at the same time as I was there, I was like, “This is insane.” But yeah, it was something that I wanted to do, and I was the one that felt scared, and I can’t speak for everybody else, but I felt scared. I felt vulnerable and ashamed and nervous, and a little bit proud at the same time.

So it’s all this whirlwind of emotions, because it’s like we’ve come this far and I feel like I know David and Joan and they’ve had such an impact on my life, but I’ve never even met them.

So it’s not quite like meeting the in-laws for the first time. But I struggled to try and give anybody a reference point, and at the same time I wanted to say thank you for helping me and holding me accountable, and I’m sorry.

And so it was just this kind of juxtaposition of feelings and emotions and things that I wanted to say.

WATKINS: Actually, can you talk… You just mentioned being accountable. Can you talk for a minute about the difference between the sort of accountability that you experienced as part of this restorative justice process with Nicola and with Joan and David? So, that accountability happening in that room and through this relationship versus the accountability or not you experienced through going to young offenders prison and the criminal justice system?

DUNNE: Yeah, well, worlds apart. The regime itself strips you of taking responsibility when you’re in prison—because you’re told when to wake up, when to go to sleep, how long to spend behind your door. You don’t make any decisions for yourself. You have no responsibilities.

So that in itself is like: how do we design prisons and run a regime in a way that encourages people to take more responsibility—not just in terms for the crimes they’ve caused, but more generally in terms of making choices for themselves, because people can’t become agents of their own life if they have no agency.

But I’m not saying that prisons shouldn’t exist. There are some people who I do believe are dangerous to themselves and other people and should be incarcerated.

And in terms of being on the outside and taking part in restorative justice, that’s allowing me to actually have some agency, to make informed choices, to hear the harm, to have the opportunity to be accountable. That’s the difference between restorative justice.

It gives you the opportunity to be accountable by listening, by acknowledging what people are saying, by writing a letter, by answering questions, by doing stuff to change your life and trying not to repeat the same mistakes, whereas custody doesn’t give you the opportunity to be accountable.

HODGKINSON: We went to court when Jacob was sentenced. So the first time we’d actually physically seen him he was in the dock, just basically looking down—we had no eye contact. And I think obviously Jacob at that point was just in total shock about what was going on.

So that was the first time we physically saw Jacob. Then the next time was when we met. And I did appreciate how hard that was for Jacob to come to that meeting. And I think, yes, the prison time was hard to serve, but just as hard to have to come and face us.

And I was nervous too–

WATKINS: Of course!

HODGKINSON: I think it’s a two-way street, it’s a very, very difficult thing to do for us as well. But again, we kind of, or I certainly, I knew because Jacob had been brave enough to come to that meeting that we were going to get somewhere. This was going to work. It’s a huge, huge thing that he did.

And you just knew if he got the guts to do that, he got the guts to do everything else.

WATKINS: But then you could have no idea then about what “everything else” would mean. We’re here in part because this dramatization of your story gets picked up by the Great British playwright, James Graham, based on Jacob’s memoir, Right from Wrong. That play, which I think is also a piece of advocacy as well for the kind of advocacy you’re doing, that opens in Nottingham where this all happened, then it makes its way to London’s West End, and now for heaven’s sake, it’s on Broadway.

HODGKINSON: It’s amazing. So we never, ever dreamt that we would be where we are, no. It’s overwhelming at times, it really is for all of us involved. And one of the big, big positives of this is that we are highlighting in the U.K. and here our great passions about the dangers of one-punch, about restorative justice.

So many plus points have come out of this. It’s got to be something that people hopefully will discuss.

WATKINS: Right, as you say, it’s not just a play. There are restorative justice circles taking place after it and discussions.

Joan and David, I believe you guys attended the Broadway production last night–

HODGKINSON: We did.

WATKINS: …and there were discussions after. Joan, what were the reactions you were getting from the audience members after?

SCOURFIELD: The audience was very, very committed to watching it. There were no mobile phones on, no rustling of sweet papers. It was very focused, very much engrossed in the play. At the end, it was a nearly full house, a standing ovation right away at the end of the show.

WATKINS: Same when I was there, yes.

SCOURFIELD: Yeah. It’s amazing to see here how it has come across. That’s how it was in Britain, but to see it here is really, really good, really good.

HODGKINSON: We did wonder, we weren’t sure coming over whether we would get a different feel from the play here. But we were just overwhelmed how well it went last night. We were given a private room so that we could talk through any points that we weren’t happy with. And there weren’t any, really, we were amazed, because we thought-

WATKINS: Come on, even the accents?

HODGKINSON: Well, they did well, we’re going to say they did really well, but we were surprised. We thought there was going to be something we were going to pull up and say, “Well, we’re not quite sure about how that’s coming across.”

WATKINS: Would I have worn that sweater?

HODGKINSON: Well, yeah.

WATKINS: But is it still a surreal experience? And obviously a difficult one too, given the subject matter, it must just be a strange feeling?

SCOURFIELD: I think the main thing is that all the actors are a hundred percent wanting to do it justice.

WATKINS: That comes across, that comes across.

SCOURFIELD: They want to portray James’s memory amazingly, and they want to make sure they get us across, with the restorative justice and everything else we want the play to come across as.

WATKINS: Jacob, you even took the American actor playing you in the Broadway production, he came to Nottingham and you took him through the Meadows and such, right? You’ve been very involved in this.

DUNNE: Yeah, yeah, I took Will Harrison around the Meadows and around Nottingham and all the main sites of the scenes in the play and was like, “Look, sit here. This is what I was going through at this moment in time.” And just trying to really kind of get him into the role and understanding, bringing those words on the script to life as much as I could.

SCOURFIELD: I’m not from Nottingham at all. So when I first went to see the play, my next phone call was, “Jacob, will you show us around the Meadows?” So I could believe that Jacob’s going to become a good tour guide for Nottingham, and we could be more famous than Robin Hood!

WATKINS: Nicola, I’m wondering where you see, you’ve been with everyone on this whole journey, how you see… How the play fits into this journey of healing and advocacy now that people are… Because I can’t imagine you’ve ever facilitated a case that led to something like this.

FOWLER: No, no. This has never happened before at all. But it’s amazing. And just as Jacob said, the cast in the U.K. and in New York have been so invested in getting this right, alongside James Graham—from a writing perspective he gave us all the opportunity to input into the play from a restorative justice perspective.

So it’s done a huge amount in terms of raising awareness of restorative justice. Us as a charity—Remedi, in the U.K.—we see more people coming forward because of it. People are picking up the phone to say, “I’ve been to see the play. I’m interested in exploring it for myself,” which is all that we could ever ask for.

WATKINS: And then in terms of the advocacy you guys are now doing, which this play is a huge jumping-off point for that as well: It seems like on the one hand you have an anti-violence message and the dangers of the one-punch homicide and encouraging young people and maybe especially young men to make different choices.

So that’s focused on individuals to some degree, but then you also are hoping for different responses from systems to crime and to harm. So it feels like to me like it’s working from both ends, so to speak. Does that sound accurate to any of you?

HODGKINSON: I think yes, you put that very well. That’s what we are trying to achieve. People are listening. I think we are getting somewhere.

DUNNE: And then there’s a third layer to this as well. The third layer is that we live in more and more polarized and divisive times.

WATKINS: Right. Difficult conversations are hard to have these days.

DUNNE: Difficult conversations are hard to have these days. And we’re becoming more intolerant of each other’s different political and religious views. And this story also can speak into that message that we can have difficult conversations in safe ways and not just dismiss each other and label each other.

WATKINS: And Joan, I mean, no one can be told to enter a restorative justice process, it’s someone’s choice, obviously.

SCOURFIELD: Completely voluntary.

WATKINS: But do you have advice, I guess, or thoughts for, say, the family of a victim, someone who might be considering entering something like this, things they should consider?

SCOURFIELD: I think you’ve got a lot to gain, I think both sides have a lot to gain from restorative justice. Okay, it’s not going to work everybody. Not everybody’s going to want to do it. Or in the beginning, we didn’t want to meet Jacob. Now we go out for lunch with Jacob! And people can’t believe that I’ll sit next to Jacob in the show, or we’ll go on screen together or whatever. People just don’t understand it at all.

WATKINS: Do you?

SCOURFIELD: Sometimes!

WATKINS: And where do we think this all goes from here? I mean, we couldn’t have predicted the West End and Broadway but-

HODGKINSON: Who knows? I mean, we keep thinking, “Well, this is it,” and then something else happens. So I don’t know really. That’s a very good question. I don’t know. We will see. Maybe there’ll be a second show about the 10 years or something.

WATKINS: But you all plan to stay together, I mean the campaign continues, the work continues that you’re doing.

HODGKINSON: Very much. We’ve got various campaigns going on. It gets quite confusing at times because we’re getting messages about all different things: “Oh, what dates are we meant to being doing such and such?” Jacob tends to be a little late at times, eh, Jacob, timekeeping?

WATKINS: We’re settling scores here in the latter part of the interview, I see!

HODGKINSON: But we joke about it.

DUNNE: But there’s a connection here, though, with the Center for Justice Innovation, and I’m glad that the Center for Justice Innovation are involved in the production of Broadway and the work that you guys do.

WATKINS: We’re honored to be a part of it, that’s for sure.

DUNNE: I want to just shout out you guys and the work that you do, in terms of innovating for justice. And you have a sister organization, which is the Center for Justice Innovation over in the U.K. And I’ve recently co-founded a new project called The Common Ground Justice Project, which Dave and Joan are senior advisors to. And by luck or by miracle, we are incubated by the Center for Justice Innovation in the U.K.-

WATKINS: Yes. I just learned that by myself the other day.

DUNNE: So we are almost like the same organization in a way. We’re distant cousins in the justice world.

WATKINS: Yes. Surprising connections abound here.

DUNNE: Yeah.

WATKINS: Well listen, it’s my understanding you have very busy schedules today, and so I should perhaps let you go. I just want to thank all four of you from the very bottom of my heart for being here, for making time, for sharing this incredibly important, and I know difficult story.

It’s one that’s already made a huge difference in the world, and it certainly sounds like it’s going to continue to make a positive difference, and Lord knows we need it.

So thank you so much, Nicola, David, Joan, Jacob, thank you so much.

HODGKINSON: Thank you.

FOWLER: Thank you.

SCOURFIELD: I just want to say thank you and thank you to everybody who’s got us this far.

WATKINS: That was my conversation with Joan Scourfield, David Hodgkinson, Jacob Dunne, and Nicola Fowler. There’s a link in the show notes to learn more about the Common Ground Justice Project that Jacob mentioned.

You can also find a link there to find out more about the Broadway production of Punch. And I’ll take this chance to urge you to attend a performance if you’re in the New York City area. It’s a truly memorable experience.

And if you’re interested in learning more about our restorative justice work here at the Center, we’ve just put out a document about using restorative justice to respond to cases of serious harm. And there’s a link to that in your show notes as well, or you can go to innovatingjustice.org/newthinking.

For their help with this episode, heartfelt thanks to the Jeff Brancato at the Manhattan Theatre Club. Thanks as well to my colleagues Kellsie Sayers, Hillary Packer, and Jullian Adler. Also to Catriona Ting-Morton and the entire communications team here at the Center.

Today’s episode was edited and produced by me, in collaboration with the Center’s communications department. It was recorded by David Herman at Brooklyn’s Good Studio; thank you to David and to Kristi Maki. Samiha Amin Meah is our director of design; Emma Dayton is our V-P of outreach, and our theme music is by Michael Aharon at quivernyc.com.

This has been New Thinking from the Center for Justice Innovation. I’m Matt Watkins. Thanks for listening.