The play, based on a remarkable true story of redemption after a one-punch manslaughter, illustrates how restorative justice can help people move forward after serious harm.

Header photo by Matthew Murphy.

James Graham’s play “Punch,” produced by Manhattan Theatre Club and directed by Adam Penford, brings an incredible true story of loss, compassion, and restorative justice to the stage on Broadway.

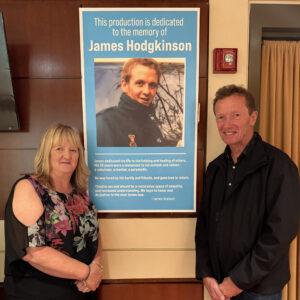

The play follows 19-year-old Jacob Dunne, who spends most of his nights partying and brawling on the streets of Nottingham, England. His thrillseeking comes to a head when he throws a single punch at another man, James Hodgkinson, outside of a bar. Nine days later, James is pronounced dead.

But Jacob’s path changes forever when he agrees to a restorative justice process with Joan Scourfield and David Hodgkinson, the parents of the man he killed. That leap of faith puts the three of them on a journey that none of them could have imagined.

“Punch” is an extraordinary story, but it’s one of many examples of how restorative justice can help people find a path forward even after the worst crises. At the Center, we’ve long used restorative justice in New York to address harm and conflict by inviting everyone involved to deeply listen to each other in a safe, controlled environment. And while restorative approaches are often used in low-level cases, we know that they offer a powerful alternative to typical responses in cases like “Punch” that involve violence and loss of life.

The play helps us see the tragic encounter between Jacob and James as part of a larger story, one of failing systems and of life choices that spiral out of control. We hear about Jacob’s upbringing in the Meadows, a public housing complex (called a “council estate” in the UK), where he’s raised by a single mother. Right beside them is the River Trent, which separates the Meadows from another, much wealthier neighborhood just across the water.

When he starts struggling at school as a boy, Jacob is diagnosed with dyslexia, ADHD, and mild autism, but receives little support from the school system. As he gets older, he feels ill-suited for polite society and takes refuge in a gang. Breaking the law becomes a mandatory part of a different code, one he strictly adheres to—be loyal, never snitch, always have your friends’ backs.

We become so concerned with survival, with protecting ourselves, that it becomes hard to feel anything else—including how our actions have affected others.

It’s a fast-paced life, reflected in the frenzied, exhilarating pace of the play’s first act—until it comes to a screeching halt. One night, Jacob gets a call from a friend saying there’s action outside a bar. He rushes over, after a night of partying and heavy drug use, and throws a punch. Then he runs.

When he finds out weeks later that the man he hit has died, Jacob admits, he’s mostly worried about himself. If that reaction seems callous, “Punch” also helps us see it as a deeply human response to a system focused more on punishment than on promoting genuine, forward-looking accountability.

That’s something our restorative justice practitioners see every day in their own work. During a traditional court process, the threat of incarceration often puts people on the defensive. When we’re afraid for our safety, we go into “fight or flight” mode. We become so concerned with survival, with protecting ourselves, that it becomes hard to feel anything else—including how our actions have affected others.

When James’s parents, Joan and David, find out that Jacob has been sentenced to 14 months in a young offenders’ prison, they push for more time. But it doesn’t help. They feel like the system doesn’t care about their needs. It’s only when they’re invited to participate in the restorative justice process that they start to get a better understanding of what those needs actually are.

“Punch” reminds us of the other people, the other lives at stake in each and every incident. The heartbroken parents, the siblings, the loved ones left to pick up the pieces—on opposite sides of one tragedy with many of the same questions.

In a post-show discussion with the audience and restorative justice practitioners, Hillary Packer—our Deputy Director of Restorative Practices—explained how restorative justice addresses victims’ need to exercise their own voice in the wake of harm. “Our criminal legal system really gives victims very little voice,” said Packer. “Their primary needs—the needs people have in order to recover, to support their healing and their ability to move forward—get sidelined.”

The same is often true for those who’ve caused harm. As he’s transported to prison, Jacob says he “feels like a package, picked up and moved from warehouse to warehouse.” What he finds when he gets there is all too familiar: violence, bravado, and little room for reflection on the harm he’s caused or what kind of life he’s going to live from here on out.

Of all people, it’s the parents of the man he killed who actually ask him that second question, during the restorative justice process. It’s a transformative moment in the story. And it’s the question that restorative justice invites us to confront: What happens next? Where do we go from here?

Like restorative justice itself, “Punch” reminds us of the other people, the other lives at stake in each and every incident. The heartbroken parents, the siblings, the loved ones left to pick up the pieces—on opposite sides of one tragedy with many of the same questions. It shows us that their needs aren’t mutually exclusive, and that genuine accountability goes hand in hand with supporting a better future for everyone involved.

When the curtains close, we can’t help but remember that the Meadows is still there. The River Trent is still flowing, the boundary between two neighborhoods with steep differences in average income and life expectancy. The kids who don’t get the support they need, the young offenders’ prison ready to take them in, the grief and loss of parents like James’s—they’re all still there. From Nottingham to New York City, restorative justice reminds us that we owe it to all of them—to James, to Jacob, to their loved ones—to patch the gaps in society that got us here. And that starts with the courage to listen to each other.