Four myths about restorative justice and what they get wrong.

As traditional responses to crime fall short of delivering the safety and healing people need, restorative justice offers a powerful alternative.

In courts, schools, and communities, restorative justice responds to conflict and harm by inviting everyone involved to speak openly about what happened and find a path forward together. It also looks beyond each individual incident, focusing on the systems that contributed to that harm happening in the first place.

But like any important reform, there are myths about restorative justice that make it hard to separate fact from fiction. Here are four common misconceptions about restorative justice and why they miss the mark.

Myth #1: Restorative justice mainly benefits people who’ve caused harm or committed a crime, not those who have been harmed.

Restorative approaches are deeply rooted in the needs of survivors, victims, and others who have been harmed. For many people, the restorative justice process is a chance to have their voices heard by the person who hurt them in a way that the typical legal process rarely allows.

The restorative process gives agency back to those who have been hurt by creating space for them to express themselves in their own words, rather than having attorneys speak for them. And it creates a deeper sense of safety for survivors and their families, who get to see the person responsible face the impact of their actions and actively make amends.

There’s an opportunity not only to get to the root of the issue, but also to have a real dialogue about how to make things better and prevent it from happening again.

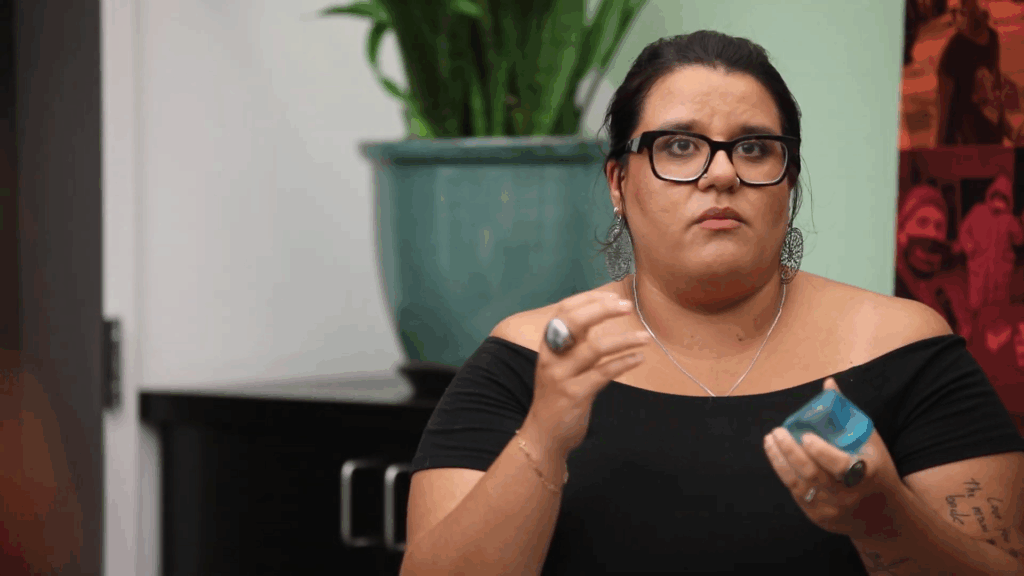

“When you send someone through the traditional legal process and incarcerate them, they’re eventually coming back to that same community without meaningful dialogue about what took place and why,” says Rachel Gregory, who oversees restorative justice programs at our Bronx Community Solutions. “In a restorative process, there’s an opportunity not only to get to the root of the issue, but also to have a real dialogue about how to make things better and prevent it from happening again.”

Myth #2: Restorative justice is a “soft on crime” approach.

Typical responses to crime often rely on a passive form of accountability, where a sentence or punishment is imposed on someone from the outside. Restorative justice, on the other hand, offers a more active form of accountability—where those responsible have to confront the impact of their actions, make amends, and work with those they’ve harmed to make sure it won’t happen again.

That can make the restorative justice process even more demanding than typical responses, which rarely require the same kind of active, wholehearted commitment to change and repair.

“Punishment is often a passive process, where you’re no longer involved in making things better or whole for the people you’ve harmed,” says Rachel Gregory. “That experience of punishment can be so distracting from your own accountability process that it takes away the opportunity to reflect or do things differently in the future.”

Myth #3: Restorative justice is only for people who are willing to offer forgiveness.

Restorative approaches recognize that forgiveness can’t be forced, and opting into the process doesn’t necessarily mean being ready to forgive. Since restorative justice is about giving those most impacted the opportunity to shape their own path forward, it’s up to those who have been harmed to decide for themselves whether they want to extend forgiveness.

“Restorative justice is a process of agency,” says Jennifer Gil Vinueza, Senior Program Manager of Restorative Practices at the Center. “It’s about giving power back to the survivor of harm to make that decision, and supporting the person who’s caused harm in understanding that that expectation might not be met.”

Myth #4: Restorative justice only works for minor offenses, not more serious ones.

Restorative justice treats harm not just as a breach of the law but as a breakdown of a relationship—the relationship we have with our loved ones, our neighbors, and our community. That makes it an inherently flexible approach, one that can be used in everything from interpersonal conflicts to serious cases involving violence.

“Some of the most impactful, restorative, and transformative spaces I’ve been in have been cases where we address serious harm,” says Vinueza. “It’s really an opportunity to heal and move forward in a human and holistic way.”

People who have suffered serious harm are often those most in need of the understanding, dialogue, and healing that restorative justice can spark. And since going through the typical court process can feel disempowering in its own right, the sense of agency and autonomy that comes with restorative approaches can be especially meaningful in more serious cases.